The Raven Sang

The raven sang

two or three times a sweet melody.

Then she saw us.

She saw me, anyway, and stopped.

We were two artists, moving into the guest house for a two-week residency at Hubbell Trading Post. I heard unfamiliar birdsong and stepped outside to see who it was. A large raven was perched on a wooden electric pole.

It was 5 p.m. in late September, that hour before real dusk when ravens fly in ones and twos all in the same direction, calling. The raven looked down at me.

"Rwork," she said and flew west. But I was sure I had heard something else first.

We were two artists, moving into the guest house for a two-week residency at Hubbell Trading Post. I heard unfamiliar birdsong and stepped outside to see who it was. A large raven was perched on a wooden electric pole.

It was 5 p.m. in late September, that hour before real dusk when ravens fly in ones and twos all in the same direction, calling. The raven looked down at me.

"Rwork," she said and flew west. But I was sure I had heard something else first.

That raven sang

two or three times a true melody.

two or three times a true melody.

I wanted to hear it again.

The same raven (or one like her) often perched on that pole near dusk during our residency. I listened as often as I could but only heard the usual range of raven evening talk, which is interesting in its own right.

Scientists have recorded over 80 distinct sounds made by ravens, though they currently believe an individual raven may use only about 20 of these on a regular basis. Sort of like I only use about 5,000 of maybe 100,000 words of common English.

Ravens have been credited with:

The same raven (or one like her) often perched on that pole near dusk during our residency. I listened as often as I could but only heard the usual range of raven evening talk, which is interesting in its own right.

Scientists have recorded over 80 distinct sounds made by ravens, though they currently believe an individual raven may use only about 20 of these on a regular basis. Sort of like I only use about 5,000 of maybe 100,000 words of common English.

Ravens have been credited with:

rrronk cluck rattle whine-thunk

caw squawk low) honk (very rapid) rap-rap-rap

coo (long rasping) caw (nasal) honk cowp-cowp-cowp-uk

kruk (low, soft, murmur/ oo-oo (soft upward inflected) cheow

krrk whisper) km and mm knock (rapid) caulk-caulk-caulk-caulk

nuk cark pruk growl

Eighty distinct sounds—plus unexpected silence. Ravens seldom speak during the breeding season until the babies hatch, and they do not call out when a captive raven is set free.

Individual ravens are known to imitate: Other birds, a train whistle, radio static, a motorcycle being revved, urinals flushing, dogs barking (near and far away) and, in the Olympic National Forest, the sound of avalanche control explosions: "One – two – three – beccccchh." But the closest I found to music in the literature was a story by Jane Kilham, wife and colleague of corvid scientist Lawrence Kilham. She heard wild ravens make sounds "similar to spring water gurgling through a tube, so musical that she found it fascinating to listen to." Perhaps there was hope for me yet.

Then, one night, I saw a PBS Nova program called "A Murder of Crows." The narrator noted that, like ravens, crows have many words, such as different cries for cat, human, and hawk, with different levels of urgency for each. They also have what the narrator called two dialects—one familiar to us and raucous, the other for private family moments which is melodic and sweet. They played 13 seconds of crows murmuring in a nest near the University of Washington, and my heart jumped. Was I getting closer to hearing that music again?

Catherine Feher-Elston tells of a bird she rehabilitated who enjoyed a music box that played "the Neapolitan classic Torno a Sorrento." She lived in northern Arizona for a while, so maybe I had heard her rehabilitated bird at Hubbell, singing an Italian popular tune. But no—Feher-Elston's bird was also a crow. I want to respect differences between these two highly-intelligent species. Because, even within each group, there are wide variations, especially in vocabulary.

Lawrence Kilham quotes a 1922 observer as saying, "Nearly every raven I met has some note that is distinctive." The Yale team of Marzluff and Angell write that raven literature reports "many unique calls with distinct meanings." And Bernd Heinrich, well-respected author of Mind of the Raven, says, "We know infinitely less about vocal communication in ravens than. . .about the call of a frog, a cricket, or the zebra finch. . . . The more complex and specific a communication system becomes, the more random-sounding and arbitrary it will appear." All of which surely allows for the possibility of music, even in a gravel-voiced songbird, right?

Distinctive notes. Unique calls. "Unique" means one time only. So why do I ask for this raven gift again? To confirm what I know to be true?

As Craig Comstock, a raven-watcher in Maine said, "I understand the need for the scientific method, but there are times when nature speaks just once, and it is a loss not to listen."

I heard a raven

sing melody sweet and true

and I treasure it.

* * *

caw squawk low) honk (very rapid) rap-rap-rap

coo (long rasping) caw (nasal) honk cowp-cowp-cowp-uk

kruk (low, soft, murmur/ oo-oo (soft upward inflected) cheow

krrk whisper) km and mm knock (rapid) caulk-caulk-caulk-caulk

nuk cark pruk growl

Eighty distinct sounds—plus unexpected silence. Ravens seldom speak during the breeding season until the babies hatch, and they do not call out when a captive raven is set free.

Individual ravens are known to imitate: Other birds, a train whistle, radio static, a motorcycle being revved, urinals flushing, dogs barking (near and far away) and, in the Olympic National Forest, the sound of avalanche control explosions: "One – two – three – beccccchh." But the closest I found to music in the literature was a story by Jane Kilham, wife and colleague of corvid scientist Lawrence Kilham. She heard wild ravens make sounds "similar to spring water gurgling through a tube, so musical that she found it fascinating to listen to." Perhaps there was hope for me yet.

Then, one night, I saw a PBS Nova program called "A Murder of Crows." The narrator noted that, like ravens, crows have many words, such as different cries for cat, human, and hawk, with different levels of urgency for each. They also have what the narrator called two dialects—one familiar to us and raucous, the other for private family moments which is melodic and sweet. They played 13 seconds of crows murmuring in a nest near the University of Washington, and my heart jumped. Was I getting closer to hearing that music again?

Catherine Feher-Elston tells of a bird she rehabilitated who enjoyed a music box that played "the Neapolitan classic Torno a Sorrento." She lived in northern Arizona for a while, so maybe I had heard her rehabilitated bird at Hubbell, singing an Italian popular tune. But no—Feher-Elston's bird was also a crow. I want to respect differences between these two highly-intelligent species. Because, even within each group, there are wide variations, especially in vocabulary.

Lawrence Kilham quotes a 1922 observer as saying, "Nearly every raven I met has some note that is distinctive." The Yale team of Marzluff and Angell write that raven literature reports "many unique calls with distinct meanings." And Bernd Heinrich, well-respected author of Mind of the Raven, says, "We know infinitely less about vocal communication in ravens than. . .about the call of a frog, a cricket, or the zebra finch. . . . The more complex and specific a communication system becomes, the more random-sounding and arbitrary it will appear." All of which surely allows for the possibility of music, even in a gravel-voiced songbird, right?

Distinctive notes. Unique calls. "Unique" means one time only. So why do I ask for this raven gift again? To confirm what I know to be true?

As Craig Comstock, a raven-watcher in Maine said, "I understand the need for the scientific method, but there are times when nature speaks just once, and it is a loss not to listen."

I heard a raven

sing melody sweet and true

and I treasure it.

* * *

This piece was performed (with raven sounds) for "The Day of the Raven"

at the Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, Arizona (November 2013)

* With gratitude to the Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site Artist-in-Residence Program, Ganado, Arizona.

* Catherine Feher-Elston, personal communication.

* Bernd Heinrich, Mind of the Raven: Investigations and Adventures with Wolf-Birds (NY: Cliff Street Books, HarperCollins Publishers, 1999)

* Lawrence Kilham, The American Crow and the Common Raven

(College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 1989)

* John M. Marzluff and Tony Angell, In the Company of Crows and Ravens

(New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005)

* PBS A Murder of Crows, video.pbs.org/video/1621910826

aired 24 October 2010

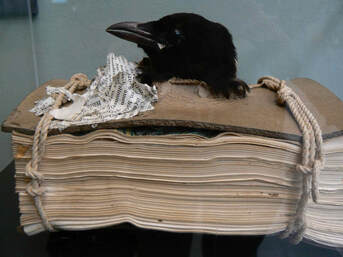

You're right -- I'm a crow, not a raven.

Photographed in a Swedish museum by David W. Hanks

Photographed in a Swedish museum by David W. Hanks