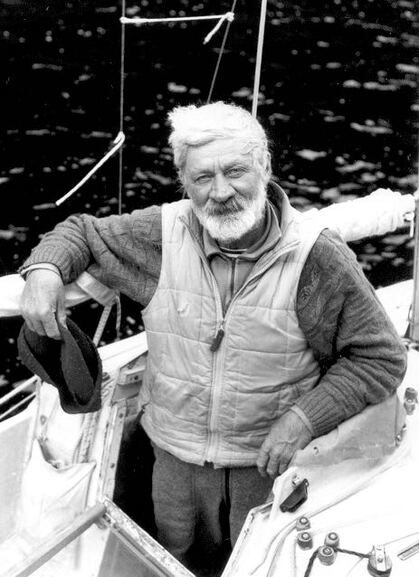

Portrait of a Cruiser: Gvogozdev Eugueni

First Russian to Sail Single-Handed Around the World

Mariners at the bottom of South America are intrepid. Some are Argentinian and Chilean Navy sailors stationed on Tierra del Fuego or Isla Navarin. Some are local fishermen with tough, beaten-up motor boats. A few are talented and creative sailors from Europe or Canada or New Zealand who are equal to the challenge of 70-mile-an-hour winds and 50-foot seas, capable of moving and anchoring among currents that run in and out of long fjords at twice the speed their well-built boats can make over the ground.

These are people who love a challenge.

One pair of these mariners were my friends Ken and Helen. They piloted their motorboat Pelagic against the prevailing current that runs along the east coast of Argentina into the territory of the Straits of Magellan and the Beagle Channel. Like all their neighbors, they were intrepid, yet invited me to visit them, knowing I am not. While I was with them in late 2000, we encountered Gvogozdev Eugueni.

Eugueni, which is “Eugenio” in Spanish, sailed single-handed around the world roughly at the Equator in four years from 1992-1996. His boat then was named Leda and was 5.5 meters long. It took him 15 years to get a passport to make this voyage and, when he finished his journey, both his boat and his passport (stamped in 26 countries) were housed in a museum in Moscow. Russia gave him a new passport, he built a new and smaller boat, and started out again on June 30, 1999.

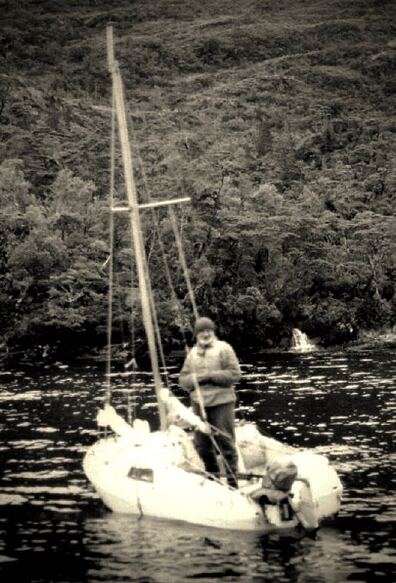

Eugueni's second boat was named Said and was 3.7 meters long. He built it on the balcony of his second-floor apartment in Majachkala, Dagestan. On Ken and Helen's boat, we had been hearing instructions to keep an eye out for Said every day on the marine weather report. (The Chilean Navy broadcasts warnings—like for a red tide or sunken obstacles—and a list of where all known boats are underway every morning before the weather. Think how few boats must be underway each day in that region!) They were asking people to keep an eye out for, "Said, 3.7 meters, a sailboat with one mast, the captain speaks no Spanish." One morning we didn’t hear the announcement and on that afternoon we saw the little boat anchored in the final difficult channel as we motored toward Puerto Natales.

Ken and Helen had known about Eugenio and his boat since Uruguay. He had spent a month at the Montevideo harbor and been written up in the Yacht Club newsletter. They did not meet him, but they had seen his boat—everyone who could get to it had. Picture it: 3.7 meters = 11.1 feet. Ken and Helen’s dinghy is 10 feet long. Eugenio's little boat was like a bobbing oval on the water, with a little mast sticking up. He was not a tiny man, either. Everyone wondered aloud how he could fit down inside the boat.

Ken motors Pelagic into the anchorage and hails Said. Eugenio’s head pops up in his wool cap. The captains gesture and shout across the water, and Ken comes down below saying Said wants a tow into Puerto Natales because he is out of gas.

Coming across the Atlantic, Said had had no motor at all, so needed no gas, benzine, naphta—all those names people call it on the southern continent. But fishermen had pitied him and got him a 15 horsepower motor for going down the coast of Argentina—going against the current like Ken and Helen did. At the bottom of South America, relying on sail to move through the turbulant channels is tricky in the extreme, so Said was forced into the expensive and dependent world of gasoline.

His trip through Tierra del Fuego had lasted about a month at the time we met him. He ran out of gas just north of the Strait. He was stranded in the complex islets and channels there waiting for favorable winds (which come seldom) when the Chilean Navy started looking for him. They had found him a couple of days before and given him a tow plus 20 liters of fuel (and taken the boat off the daily list of folks to look out for). Thus he had gotten to this anchorage. He now faced a narrow and tricky passage, where the current runs at 8 knots during both the flood and the ebb, without gas. (At top speed, Ken's motorboat can do 8 knots—most sailboats only manage 5 or 6.) So Ken agreed to tow him through and into Puerto Natales at slack tide the next morning.

Helen invites Eugenio for a hot shower and dinner that night. She puts on a big spread, including fresh fish we’d traded from some fishermen and a fabulous “Lightning Cake,” and Eugenio delivers the story he has obviously told many times around the world, in whatever mixture of languages he and his audience can paste together.

He turned 67 on March 11th of this year and is a retired ship’s mechanic. He got the idea for his first round-the-world voyage from a short article in the newpaper, describing a French sailor who had circumnavigated solo in a sailboat. Was this possible? he wondered. He looked in the library and found that many people had done this in the past 100 years—Joshua Slocum first, and then people from England, France, the US. Women had done it, even young people. But from Russia, a huge country, not one. So he decided to become the first.

His boat (judging from the way it bobbed behind us in the wind and waves) is very sturdy and buoyant, but his equipment is minimal—many think dangerously so. When he started out, he had few electronic or navigational aids. By this point in his voyage he has acquired electronics required by law in some countries: a GPS (global positioning system, which can be of hand-held size) and a marine band radio, for example. He relied on celestial navigation for his first trip, but in southern South America, cloud cover makes that unrealistic. He has a few charts and copies out information about ports where he might buy gas from books Ken has.

He seems quite healthy and I ask if he catches fish. He says no, except with a harpoon in the mid-Atlantic. He just opens a can, heats it on a camp stove and makes a cup of instant coffee, tosses the refuse overboard. He’s pretty unhappy with the weather in this region. It is cold and damp so there’s a lot of condensation in his little fiberglass bubble. He mimes water raining down on his face while he is sleeping.

“The Equator, it was nice,” he beams. “Warm. No problem!”

In Puerto Natales we get a sense of what his life is like when he’s in any port: He is a star curiosity. All day every day, people stand on the pier looking down at his tiny craft. Some even try to step on board when Eugenio is away (Ken hollers at them). He walks the two miles into town and back at least twice a day, provisioning. He reports how many liters of fuel he’s brought in that day and how many are left, that he is going to change some Deutsche marks into Chilean currency, that he just needs potatoes and onions and then he'll be ready, maybe two more trips. He decides to take as many liters of fuel as Said can carry on the next leg of his journey, and no water.

Eugueni's second boat was named Said and was 3.7 meters long. He built it on the balcony of his second-floor apartment in Majachkala, Dagestan. On Ken and Helen's boat, we had been hearing instructions to keep an eye out for Said every day on the marine weather report. (The Chilean Navy broadcasts warnings—like for a red tide or sunken obstacles—and a list of where all known boats are underway every morning before the weather. Think how few boats must be underway each day in that region!) They were asking people to keep an eye out for, "Said, 3.7 meters, a sailboat with one mast, the captain speaks no Spanish." One morning we didn’t hear the announcement and on that afternoon we saw the little boat anchored in the final difficult channel as we motored toward Puerto Natales.

Ken and Helen had known about Eugenio and his boat since Uruguay. He had spent a month at the Montevideo harbor and been written up in the Yacht Club newsletter. They did not meet him, but they had seen his boat—everyone who could get to it had. Picture it: 3.7 meters = 11.1 feet. Ken and Helen’s dinghy is 10 feet long. Eugenio's little boat was like a bobbing oval on the water, with a little mast sticking up. He was not a tiny man, either. Everyone wondered aloud how he could fit down inside the boat.

Ken motors Pelagic into the anchorage and hails Said. Eugenio’s head pops up in his wool cap. The captains gesture and shout across the water, and Ken comes down below saying Said wants a tow into Puerto Natales because he is out of gas.

Coming across the Atlantic, Said had had no motor at all, so needed no gas, benzine, naphta—all those names people call it on the southern continent. But fishermen had pitied him and got him a 15 horsepower motor for going down the coast of Argentina—going against the current like Ken and Helen did. At the bottom of South America, relying on sail to move through the turbulant channels is tricky in the extreme, so Said was forced into the expensive and dependent world of gasoline.

His trip through Tierra del Fuego had lasted about a month at the time we met him. He ran out of gas just north of the Strait. He was stranded in the complex islets and channels there waiting for favorable winds (which come seldom) when the Chilean Navy started looking for him. They had found him a couple of days before and given him a tow plus 20 liters of fuel (and taken the boat off the daily list of folks to look out for). Thus he had gotten to this anchorage. He now faced a narrow and tricky passage, where the current runs at 8 knots during both the flood and the ebb, without gas. (At top speed, Ken's motorboat can do 8 knots—most sailboats only manage 5 or 6.) So Ken agreed to tow him through and into Puerto Natales at slack tide the next morning.

Helen invites Eugenio for a hot shower and dinner that night. She puts on a big spread, including fresh fish we’d traded from some fishermen and a fabulous “Lightning Cake,” and Eugenio delivers the story he has obviously told many times around the world, in whatever mixture of languages he and his audience can paste together.

He turned 67 on March 11th of this year and is a retired ship’s mechanic. He got the idea for his first round-the-world voyage from a short article in the newpaper, describing a French sailor who had circumnavigated solo in a sailboat. Was this possible? he wondered. He looked in the library and found that many people had done this in the past 100 years—Joshua Slocum first, and then people from England, France, the US. Women had done it, even young people. But from Russia, a huge country, not one. So he decided to become the first.

His boat (judging from the way it bobbed behind us in the wind and waves) is very sturdy and buoyant, but his equipment is minimal—many think dangerously so. When he started out, he had few electronic or navigational aids. By this point in his voyage he has acquired electronics required by law in some countries: a GPS (global positioning system, which can be of hand-held size) and a marine band radio, for example. He relied on celestial navigation for his first trip, but in southern South America, cloud cover makes that unrealistic. He has a few charts and copies out information about ports where he might buy gas from books Ken has.

He seems quite healthy and I ask if he catches fish. He says no, except with a harpoon in the mid-Atlantic. He just opens a can, heats it on a camp stove and makes a cup of instant coffee, tosses the refuse overboard. He’s pretty unhappy with the weather in this region. It is cold and damp so there’s a lot of condensation in his little fiberglass bubble. He mimes water raining down on his face while he is sleeping.

“The Equator, it was nice,” he beams. “Warm. No problem!”

In Puerto Natales we get a sense of what his life is like when he’s in any port: He is a star curiosity. All day every day, people stand on the pier looking down at his tiny craft. Some even try to step on board when Eugenio is away (Ken hollers at them). He walks the two miles into town and back at least twice a day, provisioning. He reports how many liters of fuel he’s brought in that day and how many are left, that he is going to change some Deutsche marks into Chilean currency, that he just needs potatoes and onions and then he'll be ready, maybe two more trips. He decides to take as many liters of fuel as Said can carry on the next leg of his journey, and no water.

"Water is everywhere here," he says, and we all laugh.

When we first arrived in Puerto Natales with Said in tow, we all went to the Port Captain’s together to check in. They rushed Eugenio into the back with urgency. They thanked us for bringing him in and turned away.

“No,” said Ken, “you don’t understand. I have a boat, too. I also need to check in.”

This kind of notariety is helping Eugenio make his way. His visa ran out during the 300 miles of his passage through Tierra del Fuego. (Russians are only given one-month visas, while North Americans and most Europeans get three months.) His next renewal is likely to be late as well, since the distance to the next visa-granting town is 1000 miles.

“No problem!” says the intrepid Gvogozdev Eugueni. “I look at them, they say, ‘I see you on TV!’ They see small boat, old man—new visa? No problem!”

* * *

When we first arrived in Puerto Natales with Said in tow, we all went to the Port Captain’s together to check in. They rushed Eugenio into the back with urgency. They thanked us for bringing him in and turned away.

“No,” said Ken, “you don’t understand. I have a boat, too. I also need to check in.”

This kind of notariety is helping Eugenio make his way. His visa ran out during the 300 miles of his passage through Tierra del Fuego. (Russians are only given one-month visas, while North Americans and most Europeans get three months.) His next renewal is likely to be late as well, since the distance to the next visa-granting town is 1000 miles.

“No problem!” says the intrepid Gvogozdev Eugueni. “I look at them, they say, ‘I see you on TV!’ They see small boat, old man—new visa? No problem!”

* * *

photos of Gvogozdev Eugueni and South Chilean Channels © Phyllis L. Thompson